FireFall Vol. 20: Women Shaping the Church

It's Women's History Month! *This newsletter may leave confetti fluttering in your inbox*. Get ready to be inspired, equipped, and occasionally, yes, amazed, because history is *never* boring.

There were things about my Grandma I only learned at her funeral. Naturally, I couldn’t ask her about them. It was my youngest child’s first funeral. Despite a fair amount of preparation, she peered toward the front during the service and whispered - rather loudly - “I hope she’s okay!” Grandma would’ve found it hilarious. I was tempted to answer, “well, I’ve got good news and bad news…”

Why on this earth would I start off women’s history month with a story about a family funeral?

Because this - in part - is what history is.

History is archaeological layers and quilts, eyewitness accounts and pottery shards, photos and documents, hats and tombs.

Sometimes history primarily is people: we exist because our ancestors survived long enough for us to exist. We are the evidence.

And sometimes, history is sharing stories at a funeral.

When I delve into digitized archives or open access digital books that make womens’ stories accessible in historically unprecedented ways, I often end up feeling like I did at Grandma’s funeral: I knew her, and I didn’t know her.

I had a fairly decent grasp of church history (especially but not solely in the global West; I knew some of the currents of church history around the globe). And yet.

I am moved by early 20th-century photos of a woman from India preaching in a village; I am moved by accounts of Chinese-Australian preacher Mary Yeung, who planted multiple congregations in China and Hong Kong.

I chuckle, applauding a brilliant nun from Mexico: Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz defended her “secular” scientific study in the 1600s, writing “one can perfectly well philosophize while cooking supper.” I chuckle at the American Depression-era holiness preacher Rev. Emma Irick, who put on her absent husband’s overalls and climbed onto the parsonage roof to patch the many leaks. She and her husband were once asked to hold a service down in an Alabama coal mine. She preached in the lantern-lit gloom; miners came forward for the altar-less altar call.

I chuckle at Englishwoman Mary Astell writing in 1705, “since the Men being the Historians, they seldom condescend to record the great and good Actions of Women; and when they take notice of them, ’tis with this wise Remark, That such Women acted above their Sex. By which one must suppose they wou’d have their Readers understand, That they were not Women who did those Great Actions, but that they were Men in Petticoats!”

I stare at grainy black and white archival footage of a Church of the Nazarene general assembly in the 1920’s; unaccustomed to “moving pictures,” attendees stop and pose as though they’re standing for a photo. Then, there she is: Rev. Santos Elizondo captured in film.

It’s not just interesting trivia.

When I read some of the spiritual autobiographies of women preachers, I feel their steel strengthen my spine. When I read of their struggles to discern the direction and movement of God, I recognize contours of my own journey.

When I see photos and paintings of women from around the world, women of color, who were preachers, evangelists, church planters, I see photos of majority-world women leading: portraits of what leaders look like.

How do you picture the story of the church? How do you picture church history?

How do you picture the Protestant Reformation?

Six years after Luther pinned his theses to Wittenberg social media, “In 1523, in one of the most daring and remarkable events in the history of the Reformation, a woman challenged the Catholic establishment to a public debate. The issue was the persecution of a young Lutheran student in Ingolstadt. Argula von Grumbach's writings on this and many other topics were widely circulated…” (Peter Matheson)

Where do we look for portraits of women?

Sometimes, in tombs.

The first book mentioned below addresses women and authority in early Christianity. Here’s part of the summary: “Most people have never heard of Bitalia, Veneranda, Crispina, Petronella, Leta, Sofia the Deacon, and many others even though their catacomb and tomb art suggests their authority was influential and valued by early Christian communities. This book explores visual imagery found on burial artifacts of prominent early Christian women.”

I knew her, and I didn’t know her.

At my Grandma’s funeral, I learned the steely, gardening, sewing, piano-playing, Sunday school-teaching, Pilgrim Holiness/Wesleyan pastor’s wife once stepped in for Grandpa for several weeks while he was sick, preaching with baby in one arm, Bible in the other hand.

These are the stories of who we are, and they’re worth celebrating. These are the testimonies that bear witness to the mighty works of God; the testimonies that reverberate through the centuries. Sometimes they’re intensely practical and instructive; sometimes theologically rich; sometimes inspirational and profoundly challenging.

I give thanks for these women - and for the joyful men who sacrificed to help preserve their history and testimonies (like Rev. Paul Dayhoff, celebrating the ministries of African women); who chose to elevate rather than bury womens’ archival materials (like Stan Ingersol); who fiercely advocated for women (like Rev. Seth C. Rees and Rev. B.T. Roberts); who harnessed the horses and spent hours in all weather driving their preacher-wives to appointments (like Brother Hickox in the 1830s); in one case, who turned down a district superintendent position to which he’d been elected, calling a woman to say he’d been fasting and praying and could not get peace because he knew she was supposed to be in the role, not him: he didn’t know she’d been fasting and praying because she couldn’t get peace ever since she refused to be considered for the role (hero Rev. Junior Sorzano, calling Rev. Rosa Lee); who as pastors supported their wives’ ministry (like Rev. Manuel Tshambe, whose wife pastored a church that grew to several thousand members); who recognized anointing even though they were against women in the priesthood (like Bishop Ronald Hall, who ordained Rev. Florence Li Tim Oi); who encouraged their daughters to preach and gave them opportunity to practice (like Rev. Dr. Ella Pearson Mitchell’s father); who against a rising tide advocated for clear language and strong policy regarding pastors who abused their positions and power (like my Grandpa); who wrangle very young children on Sunday mornings while their wives preach, or who sometimes at the end of the work day make supper while their wives are hyper-focused on women in church history (my husband John).

When I’m elbow-deep in the histories of women ministers, there’s a lot to make my blood boil; and it’s a breath of fresh air to name and honor the honorable.

Read: Crispina and Her Sisters: Women and Authority in Early Christianity; Women of Jeme

As mentioned above, from Catholic scholar Christine Schenk CSJ, Crispina and Her Sisters: Women and Authority in Early Christianity, “carefully situates the tomb art within the cultural context of customary Roman commemorations of the dead. Recent scholarship about Roman portrait sarcophagi and the interpretation of early Christian art is also given significant attention. An in-depth review of women‘s history in the first four centuries of Christianity provides important context. A fascinating picture emerges of women‘s authority in the early church, a picture either not available or sadly distorted in the written history. The portrait tombs of fourth-century Christian women suggest that they viewed themselves and/or their loved ones viewed them as persons of authority with religious influence.”

In reviewing this 2017 book, the Catholic Press Association remarked, “While making no theological claims, and emphasizing the historical character of the research, this book will contribute to the accumulating evidence that women’s roles in the 21st century Church should be reevaluated, because it was not until the fourth century that women’s ecclesial authority was restricted to monastic settings. This book is very well explored, well organized and quite readable.”

From Dr. Terry Wilfong comes Women of Jeme: Lives in a Coptic Town in Late Antique Egypt. In this 2002 work from the University of Michigan Press, “Get to know the women of Jeme, a Christian enclave in Egypt that existed from 600 to 800 C.E. Using texts documenting the women's activities, the physical remains of their possessions, and the writings of the local religious leaders, T. G. Wilfong traces the lives and careers of individual women and, through them, arrives at an understanding of the reality of women's lives in this place and time. Contrary to the submissive, demure ideals for women proposed by the religious writers of Christian Egypt, the evidence from Jeme points to a more complex, dynamic situation. Women were active in the home, but some also played important and visible parts in the religious and economic life of their community.”

The summary shows the “synthetic” approach taken across disciplines: “It will be of interest to Egyptologists and papyrologists, as well as to scholars of Coptic studies, early Christianity, social history and women's studies. The book assumes no prior knowledge of the subject, and the author has taken care to make it accessible to anyone with an interest in the ancient world.”

Dr. Mabel Ping-Hua Lee (李彬华): Economist, Suffragist, Baptist Pastor

Dr. Mabel Lee (1896-1966) wrote in support of womens’ suffrage, rode in a parade with famous leading suffragists, but when other women in the state of New York “got the vote,” Dr. Lee did not, because she was Chinese American.

Her father had established a mission in New York’s Chinatown; Mabel Lee blazed through her education, earning a PhD in economics. She had lucrative job offers in prestigious roles.

And when her father suddenly died, Dr. Lee turned down those offers and took over the mission, raising funds to buy the building at 21 Pell Street, where she founded the First Chinese Baptist Church. She preached every Sunday, hosting practical classes and services for the Chinese American community.

She led that Baptist congregation for 40 years.

And 21 Pell Street is still the First Chinese Baptist Church.

Read more here by Dr. Tim Tseng.

Women Evangelists of Tamil Nadu, South India: 1922, 1942

I’m so thankful to find some photos of “Bible women” that name the women. Some do; some don’t. These archives from a Danish mission in Tamil Nadu (South India) also rightfully title the women in this photo evangelists. That’s what they were.

But Western missionaries were often called missionaries while indigenous women were called Bible women. Yes, it’s loaded.

Western missionaries were often of European descent (though not always; some African American women were missionaries. Amanda Berry Smith preached to white camp meetings in the U.S. and also spent two years as an evangelist in India, later preaching in western African countries as well).

This picture-postcard below was taken twenty years after the one above, in 1942; it doesn’t provide a name for the woman evangelist visiting a village. Was she part of the 1922 photo? I don’t know.

The phrase Bible women is complex, as this well-sourced Wikipedia (how times have changed!) entry sketches. Early on the phrase “Bible women” referred to women in London from poor backgrounds who could help physically and figuratively guide the efforts of an earnest woman who was determined but from a very different background. She needed the help of those who knew the terrain - and who could perhaps more quickly gain trust. (If you’re upper-middle class and visiting a trailer park, it’s helpful to have the assistance of someone who grew up in a trailer park.)

The history of missiology is complex at the best of times. To 19th and 20th century women of the global West, becoming a missionary could be a way to minister and preach that was somewhat socially acceptable to those in their home settings. At the same time, before or at the cusp of globalization, lack of cross-cultural exposure or experience could be a real liability. These were largely days before even movie theatre news reels, when world travel took weeks or months at sea.

Indigenous Bible women preached, led, and evangelized. It’s good to title them evangelists. It’s even better when we can name them: Lydia Mathæus, Soranam Aaron, Susannal, Mercy, Parandjodi.

I love Mercy’s smile.

(Visit here to learn more about very early Christianity in India and the Mar Thoma church.)

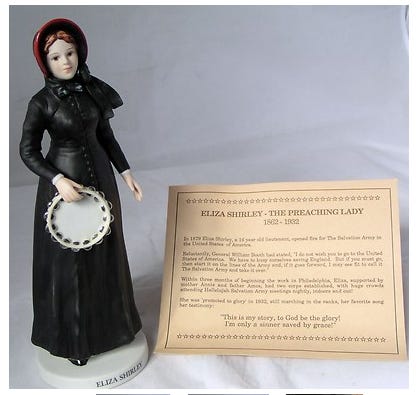

…The Salvation Army Came to the U.S. because of a Teenager?

I admit I was caught off-guard when I learned that a teenage girl helped spearhead the movement to bring the U.K.-based Salvation Army to the United States.

Women leading in the Salvation Army - that, I’m not surprised by. I just didn’t expect a teenager.

The 1800s weren’t easy years for the Salvation Army in the U.K. or the U.S.; they were the physical-threat years, the mud-in-the-face years, harassment-from-the-skeleton-army years, the whoa-one-woman-who-was-a-Captain-in-the-Salvation-Army-died-due-to-injuries-sustained-from-a-mob years.

Well-off teenaged Eliza Shirley asked William Booth to push the movement to America, and with her parents launched Salvation Army efforts in the U.S.

“The first successful work in the United States rested on the shoulders of a 17 year old girl. In the spring of 1879, the newly named Salvation Army in London was so small that all the workers knew each other personally. Eliza Shirley, then 16, joined the Christian Mission and was appointed as an evangelist at one of the ‘stations.’ At first, her parents, Amos and Annie Shirley, were not sure they approved. Shortly thereafter, Amos, an experienced silk weaver, left for America and found a position in Philadelphia. Eliza did not want to leave the Army behind. She called on General Superintendent William Booth and asked permission to start the work in America.

By then, she had been commissioned a lieutenant. Booth was not sure the U.S. was ready for opening. However, he softened enough to say that if she were unable to resist, she could go with his blessing. Further, if she were successful, he would give her work official recognition.

By the time they reached Philadelphia, her mother shared her desire to begin Army work. They walked the streets looking for an affordable meeting place, finally settling on an abandoned chair factory. Posters announced the appearance of ‘Two Hallelujah Females.’ People flocked out of curiosity. Their trophy was Reddy, the worst drunk in the area. When the people saw Reddy march to the hall, they followed to see what they would do with him. News of Reddy's conversion reached not only the local papers, but up and down the coast. General Booth's reply to the American success was the promotion of the Shirleys to captain.”

Eliza Shirley continued her ministry, eventually marrying Captain Phillip Symmonds and becoming a mother of four. She developed a love of baseball and was a known and committed Cubs fan. In her eighties - the 1930s - while she was on her deathbed, “the Cubs were in the final games of the World Series. She drifted in and out of consciousness, alternately praying and asking how the Cubs were doing.”

To my knowledge, she’s the only woman preacher for whom a moment of silence was taken during a major league baseball World Series.

The Sacred Fire

Dr. Dorothy Graham wrote a dissertation on women itinerate preachers of primitive Methodism in Great Britain, and I’m astonished at how much data she combed through. She has a real database of a website on these early Methodist women preachers.

In any event, her dissertation includes citation for this sweet little poem written in the 1820s:

THE SACRED FIRE

The sacred fire doth burn within

The breasts of either sex the same;

The holy soul that’s freed from sin,

Desires that all may catch the flame.

This only is the moving cause,

Induc’d us women to proclaim,

‘The Lamb of God.’ For whose applause,

We bear contempt-and suffer pain.

If we had fear’d the frowns of men,

Or thought their observations just,

Long since we had believ’d it vain,

And hid our talent in the dust.

Knowing our labours have been blessed,

(However plain our words have been)

We are determin’d not to rest;

But strive to save poor souls from sin

The Female Preachers’ Plea (written originally by the wife of W. O’Bryan); Primitive Methodist Magazine (1821) pp. 190-192

Thank you for subscribing to FireFall, a weekly ecumenical newsletter amplifying the voices of women leading in pastoral ministry and theological education around the world throughout history and today.

Resources curated by Elizabeth Glass Turner. Daniela Galindo-Cabrieles generously donates her time and skills for the translation of these resources into Spanish.