FireFall Vol. 22: Voices Rising

Rev. Tatum Osbourne at Women Clergy Conference, World Day of Prayer for Women's Ordination, Candida Xu: Apostle of China, and Pastor's Husband Mug

Welcome to FireFall! It’s Eastertide, and I hope you’re spying signs of new life as grace unfurls in unlooked-for places.

Re-Cap: Rev. Tatum Osbourne at Wesleyan Holiness Women Clergy Conference

Around 800 clergy women representing multiple denominations gathered in March in Grapevine, TX for the Your Daughters Will Prophesy 2024 Wesleyan Holiness Women Clergy Conference. Several days were packed with worship, fellowship, powerful plenary worship sessions, and practical workshops. This year, the plenary sessions were livestreamed free of charge - a gift for many who couldn’t attend in-person. (FireFall translator Pastora Daniela Galindo-Cabrieles helped host the livestream!)

Conference livestream content is still available over on YouTube - click here for a Spanish workshop session, watch Rev. Christine Youn Hung’s keynote address here, or browse the entire 2024 conference playlist here.

For now, I’ll highlight this sermon from Rev. Tatum Osbourne: if you need a word, and especially if you need a word of encouragement, soak in this. One word comes to mind from this sermon, and it makes me want to listen all over again: “push!”

The next conference will be in 2026. Visit here for more from WHWC.

Our Catholic Friends: The World Day of Prayer for Women’s Ordination, on the Feast of the Annunciation

On March 25th, a group of Catholics marked the Feast of the Annunciation as the World Day of Prayer for women’s ordination.

They do this every year, crafting some beautiful prayers and liturgies.

Here’s one used in March this year.

It is extraordinary and beautiful to me, to watch an ecumenical tide surging across Orthodox, Catholic, and Protestants, as voices begin to echo and amplify and carry louder, and louder, and louder, like the voices of the women running from the empty tomb.

I can think of few more beautiful gifts for Protestant women to give those of our Catholic friends who’ve been working for women’s ordination for decades, than to mark our calendars and join them in prayer for this every March 25th.

I hope you’ll take out your smartphone or planner and add it to your calendar.

To support in a tangible way, you can check out these Ordain Women shirts from womensordination.org.

You can also visit Women’s Ordination Worldwide at womensordinationcampaign.org.

Explore an extraordinary amount of research at womenpriests.org

Meanwhile, the Pope announced that the April prayer intention for the Roman Catholic church is for “the role of women” - read more here from Vatican News.

Candida Xu: “Apostle of China” and Patron of Jesuit Mission

Candida Xu (許徐甘弟大 1607-1680) was born in China in 1607, was baptized as an infant, and was raised a Christian.

The Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Christianity provides this snapshot: “Xu, a granddaughter of the eminent convert Hsu Kuang-chi (1562-1633), was deeply religious from childhood. After she was widowed at the age of 46, she dedicated herself to serving the church. With zeal and ingenuity, undeterred by the restrictions the secluded life of an upper-class woman in traditional Chinese society placed on her, she worked to spread Christianity in China.”

While Candida Xu was not a preacher (at least in the way Protestants typically think of preaching) she was however a leader. Within the 17th-century framework of both her Catholic faith and her prevailing cultural context, after she was widowed she leveraged her freedom to wield considerable influence. In fact, when I read about her considerable activity, business sense, and the depth of her significant patronage, some New Testament names come to mind: names like Joanna and, later, Lydia.

Consider her extensive influence, further outlined in the BDCC: “She promoted the work of lay spiritual associations among Chinese Christians and was the leader of Christian women in the Shanghai area. Having by diligence and thrift raised a private income, she donated generously to the living expenses of the missionaries, financed the building of nearly forty churches and chapels, and funded publication of many Christian doctrinal and devotional works in Chinese.”

Scholar Gail King explains, “The constraints that traditional Chinese society placed on women were many, but Candida Xu never let them deter her from putting into practice her Christian beliefs. A faithful wife and mother of eight who was widowed at the age of forty-six, she devoted the remaining twenty-five years of her life to service to God. She supported missionaries, financed construction of churches and chapels, underwrote printing catechisms and devotional materials, gave generously to the poor, sent relief to the sick, provided burials for abandoned infants and the destitute, and was a leader of Chinese Christian women.”

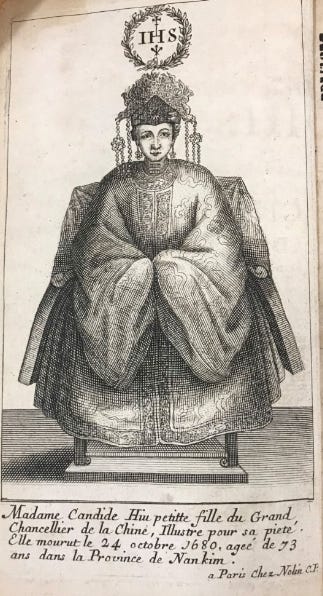

In the introduction to the 2018 Jesuits and Matriarchs: Domestic Worship in Early Modern China, Nadine Amsler describes some of the artifacts that made their way from the hands of an elite Chinese woman to Europe:

“In 1682 the Flemish Jesuit Philippe Couplet returned from a twenty-two-year stay in China. He arrived in Holland with heavy luggage. Among his many objects were several gifts donated by Candida Xu (1607–1680), an eminent Catholic lady of Songjiang (today part of Shanghai city). The gifts included textiles, such as Mass vestments and altar cloths embroidered by Candida and her daughters; richly ornamented altar vessels made from precious material; and ‘four hundred volumes in Chinese written by the Jesuit missionaries, the purchase of which was financed by Candida Xu.’ These gifts were destined for the pope and well-known European churches. Couplet’s luggage likely also contained a first draft of a book on the pious life of the China mission’s female patron: The Story of a Christian Lady of China, Candida Xu (Historia Nobilis Feminae Candida Hiu, Christianae Sinensis).”

Did she have a sense of vocation? That’s perhaps not the right question for her context, or at least, it’s perhaps a difficult question; but it’s clear she had a deep sense of piety. In the global West, we know of Candida Xu primarily through her Jesuit confessor Philippe Couplet’s book about her, written in part to strengthen appeal for continued European support of Jesuit mission work in China.

I wish we had a memoir by Candida Xu; there is inherent distance between subject and writer, limits to what we can know about her internal world and even limits to what we can know about the shape of her spiritual leadership among other women.

However, I’m thankful to have any book about her - and in addition to Couplet’s book, her son Basil Xu Zuanzeng also wrote a biography about her. Scholar Gail King writes, “Fr. Couplet’s biography, published first in 1688 in French and later in Spanish, Flemish, and Italian versions, is the fullest account of Candida Xu’s life and even now, even in China, is the main source of information about her. From its pages we learn nearly all that is known of her life.”

We owe a great deal to Gail King, who has carried out an extraordinary amount of research into Candida Xu’s life, family, and historical and cultural context. Her work ranges from scholarly articles like “Candida Xu and the Growth of Christianity in China in the Seventeenth Century” to a fresh biography that draws on Couplet’s work but also integrates the biography by Xu’s son Xu Zuanzeng, as well as archival family records (see a review of King’s biography here).

Though the distance of an outsider looking in persists, there is something touching and personal in Couplet’s account of the funeral rituals carried out for Candida Xu. While they’re of multidisciplinary interest in terms of intercultural studies, contextual theology, history, and more, the descriptions are both vivid and visceral.

Nicholas Standaert writes in The Interweaving of Rituals: Funerals in the Cultural Exchange between China and Europe, “As related by Philippe Couplet, the main role at this condoling was assigned to the son of Candida, Xu Zuanzeng…

‘Her son, Sir Basile, who had been with her since some time, and who disposed of all his assignments with permission of the emperor in order to express the final duties to her, went into mourning, which lasts for three years; it is a dress of coarse tissue in white, which is the colour of mourning in China, with a cord as belt and grass sandals. In this lugubrious dress he prostrated himself three times before the body of his good mother, and touched the ground with his forehead nine times, shedding tears over the loss he came to experience, and the whole family did the same after him.’”

Standaert explains the mourning clothes indicate Candida Xu’s son observed the “first degree of mourning” typical for the elite of the time and places the practices as typical for the context. Again, he quotes Couplet:

“After the body was put in the magnificent coffin…he composed a eulogy…which he had printed to be sent to all mandarins, and to literati. At the same time a table covered with a large white cloth, burning candles and incense was installed in the room where the body was laid out behind a white curtain, which also covered the place where the women were crying. The Portrait of the Lady was spread out on the white curtain; it is this image that is also carried in the funerary ceremony…”

Couplet continues, “Officials of all classes came with ceremony to pay the last honors to this corpse, following the practice of China. They first entered in a hall, where, after having left their ceremonial clothing for a white robe, they advanced with presents, which are incense, pieces of white silk, candles of particular wax made by ants…they prostrated themselves before the white curtain, beating their head against the earth…Sir Basile came from behind the curtain and prostrated himself before them, beating three times his head on the earth…this ceremony lasted several days, after which Sir Basile went in his mourning clothes all over the city of Songjiang, preceded by a master of ceremonies, to make the same genuflections, and same beatings of the head, only at the door of the palace of each mandarin on a white carpet spread…”

Candida Xu, “Apostle of China,” was honored well: may she rest in peace and rise in glory.

If you can read French, you can browse a digitized version of Jesuit missionary Philippe Couplet’s 1688 biography of Candida Xu here.

“Pastor’s Husband” Mug from The Drinklings Coffee Shop

You may know a ministerial spouse who could use this mug:

From The Drinklings Coffee Shop in Wilmore, KY, this mug is for every gentleman (my husband included) who’s had to say, “no, actually…” to an embarrassed, baffled stranger who’s doing a double-take. You don’t have to drive to the Bluegrass for one of these - just visit here.

Thank you so much for supporting FireFall!

FireFall is a warmly ecumenical newsletter amplifying the voices of women leading in the church and academy, around the world and across time. It was launched in fall 2023 by Elizabeth Glass Turner. Pastora Daniela Galindo-Cabrieles generously donates her time and skills for the translation of these resources into Spanish.