On Prophetic Nudity

On women's preaching, church history, Calvinism, Liberia, and the Nobel Prize

What, you may be wondering, have I signed myself up for?

This topic is not pulled from salacious headlines.

It’s pulled from church history.

While it’s true the topic of prophetic nudity makes me chuckle, I’m inviting you to consider it with me for a bit because it’s such a fascinating hub from which to connect multiple constellations of thought.

Prophetic nudity: the ideal multidisciplinary discourse?

But if I can make myself laugh, think about women in church history, consider multidisciplinary facets, and provoke a bit of thought - all on a snowy day with a cup of loose black tea within arm’s reach - well, day made.

I do hope this prompts some engaging conversation, because those with deep expertise in some of the relevant disciplines can, I’m sure, shed some helpful light on an often blanketed topic.

If People Think You’re Too Much: Just Remember Brekus on Puritans, Women, Quakers, and Prophetic Nudity in the 1600s

I’m a little sad that only in the past few years have I learned a couple of things: one is that a woman preacher was executed in the American colonies before they’d even become the United States. Mary Dyer was hanged in Boston in 1660 (more than one hundred years before the American Revolution, and more than forty years before Susanna Wesley’s famous letter to her husband Samuel), and I think every American ministerial student–regardless of their theology–should know about Mary Dyer. Another thing I wish I’d known: some Quaker women in the colonies had a fascinating practice.

Yes, you guessed it: prophetic nudity.

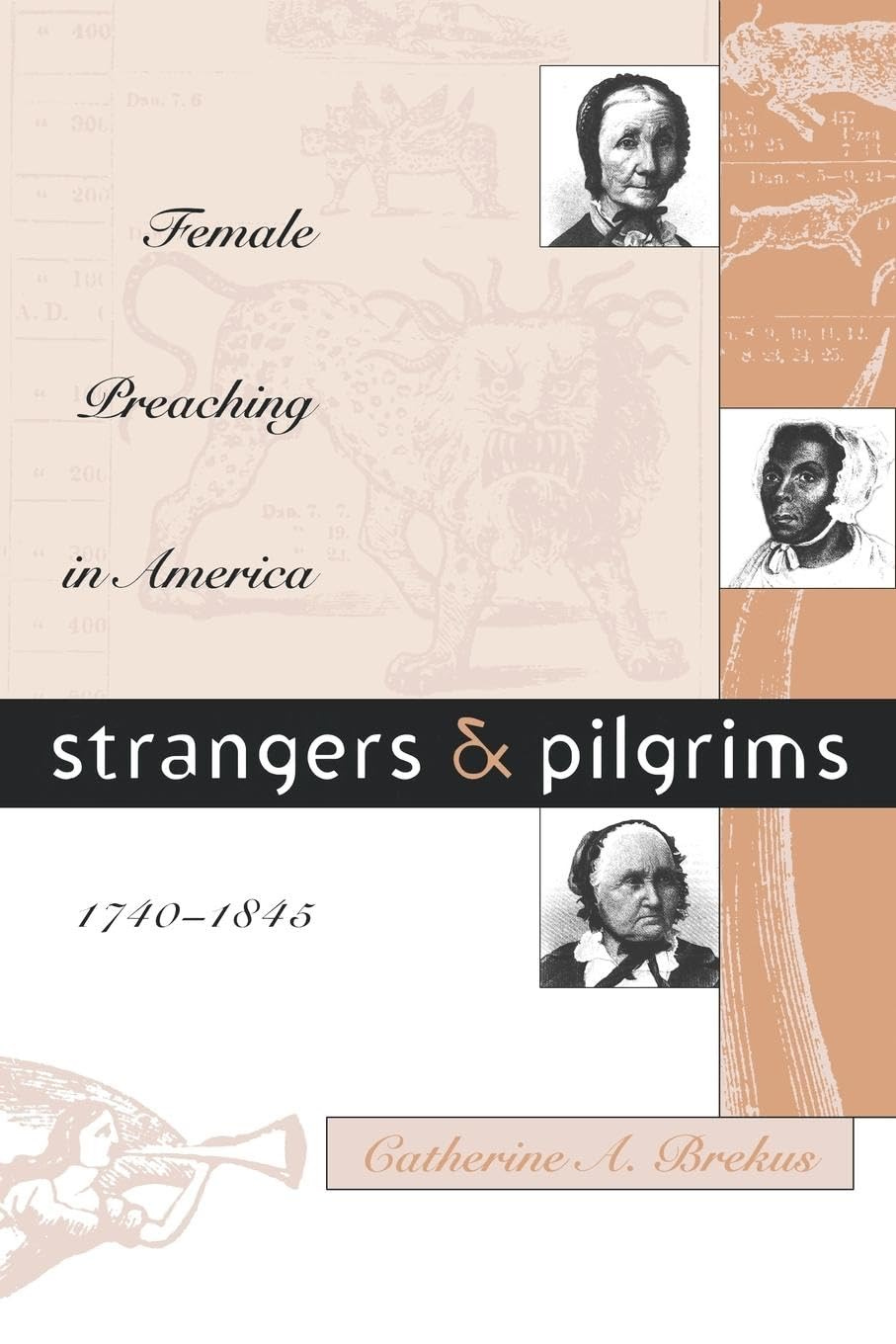

In her 1998 Strangers and Pilgrims: Female Preaching in America, 1740-1845, Dr. Catherine A. Brekus summarizes practices before that span of time. Commenting on Quakers in the 1600s, she writes,

“The Puritans' darkest fears about the dangers of uncontrolled female speech seemed to be confirmed by the Quakers' "lewd" custom of "going naked as a sign." Modeling themselves on the prophet Isaiah, they stripped off their clothes in public, sometimes even in the aisles of churches, as a protest against their treatment by Puritan authorities. Such behavior seemed to offer concrete evidence that female preaching would inevitably lead to sexual as well as religious disorder. As John Cotton explained, a woman who was allowed to speak or testify in the church "might soon prove a seducer." Tellingly, his choice of words explicitly linked "unbridled" female speech to heresy and promiscuity, sins that had to be swiftly punished if the holy commonwealth were to survive. Indeed, after Deborah Wilson appeared naked in the public square in Salem, she was forced to walk half-clothed through the streets pulling a garbage cart, a constable lashing her from behind.”

Quaker women had also been flogged in Cambridge, England; and Quaker men were also hanged in Boston – some of Mary Dyer’s friends, in fact. So it wasn’t just in the colonies that Quakers faced persecution, and it wasn’t solely Quaker women who faced public punishment or execution.

It fascinates me that prophetic nudity was practiced as a protest against their treatment by Puritans, and that prophetic nudity was practiced based on the prophet Isaiah: in other words, from a scriptural basis.

If you’re a woman who preaches, if you’re a woman in church leadership, and sometimes people imply that you’re a bit much, please: stop and remember that in Massachusetts in the 1600s, women were going naked publicly as a prophetic sign, take a deep breath, smile, and weigh the idea of dropping that little historical tidbit at strategic moments to prompt a bit of renewed perspective.

Isaiah 20, Prophetic Nudity, and the Doom of Nakedness

In the Quakers’ hermeneutic of nakedness, a woman’s bared flesh seems unlikely to have been the sole provocation to the Puritans (after all, a constable walked Deborah Wilson only partially clothed for her garbage cart whipping). Isaiah 20 is brief, potent, and to the point: here’s a large excerpt of the chapter.

At that time the Lord had spoken to Isaiah son of Amoz, saying, ‘Go, and loose the sackcloth from your loins and take your sandals off your feet’, and he had done so, walking naked and barefoot. Then the Lord said, ‘Just as my servant Isaiah has walked naked and barefoot for three years as a sign and a portent against Egypt and Ethiopia, so shall the king of Assyria lead away the Egyptians as captives and the Ethiopians as exiles, both the young and the old, naked and barefoot, with buttocks uncovered, to the shame of Egypt. And they shall be dismayed and confounded because of Ethiopia their hope and of Egypt their boast. On that day the inhabitants of this coastland will say, “See, this is what has happened to those in whom we hoped and to whom we fled for help and deliverance from the king of Assyria! And we, how shall we escape?”’ (NRSV-A)

The messaging here from the Quakers to the Puritans is loaded, to put it mildly. One doesn’t have to be a biblical scholar (and I am not) to gather that the context for Isaiah’s prophetic nudity is doom. How did the King James Version render part of this passage?

“And the Lord said, Like as my servant Isaiah hath walked naked and barefoot three years for a sign and wonder upon Egypt and upon Ethiopia;

So shall the king of Assyria lead away the Egyptians prisoners, and the Ethiopians captives, young and old, naked and barefoot, even with their buttocks uncovered, to the shame of Egypt.”

The Quakers went naked as a sign against the Puritans. The Puritans read it as shame and shameful, and reinforced this with actions like driving Deborah through town with a whip as she pulled–let’s be honest, at best just garbage in a garbage cart.

Who is doing the dooming? Who is being doomed? What’s shameful, a woman naked in the town square, or whipping someone while forcing them to haul garbage?

I imagine if I’m being paraded through town, pulling smelly trash, being struck on the back until my back is bruised, cut, swollen, and bleeding, I might find it challenging to counter the immediate, local picture and narrative that I am the one who is doomed. On the other hand, if that’s me, I probably haven’t entered the town square naked as a jaybird without considering the possibility of potential repercussion.

Norms, Antinomianism, New Calvinism, and Pneumatology and Nudity in the New World

“New World” is solely for the wordplay rollercoaster, the land of those colonies wasn’t new, and neither were the indigenous people who’d been living there.

Let’s consider a few things regarding the prophetic nudity of the Quakers in the 1600s.

First, a note on privacy generally considered. Whatever mental picture one has of life a few centuries ago, keep in mind that only six or seven decades ago, it was common for homes in American small towns to have outhouses in the backyards, and you might espy neighbors’ heads hurrying out to them in the dim chilly morning light. In Amish-heavy parts of the U.S., a drive down a country highway means the sight of someone’s laundry flapping in the breeze or hanging out on the porch, pants and sheets drying for all to see. And in London mid-1800s, the need for a sewer system was so bad that action was taken after the “Great Stink” of 1858, when a heat wave warmed up the Thames and the air smelled so foul it interrupted parliament. Expectation of privacy generally speaking varies in many parts of the world, across cultures, across classes, and across time. The realities of life really weren’t so distant.

Second, a note on antinomianism. Brekus masterfully summarizes a great deal in her comment, “Such behavior seemed to offer concrete evidence that female preaching would inevitably lead to sexual as well as religious disorder. As John Cotton explained, a woman who was allowed to speak or testify in the church ‘might soon prove a seducer.’ Tellingly, his choice of words explicitly linked ‘unbridled’ female speech to heresy and promiscuity, sins that had to be swiftly punished if the holy commonwealth were to survive.”

The threat of disorder and lawlessness: prophetic nudity isn’t so much against the Calvinistic Puritanical patriarchal mistreatment, it’s what happens when you allow women to speak in church. If a woman speaks in church, everything falls apart.

Diane Willen summarized some Calvinistic Puritanical patriarchal assumptions in this little tidbit from 1622: “William Gouge, in his widely read Of domesticall duties, even argued that the husband ‘is as a Priest unto his wife, and ought to be her mouth to God when they two are together’” (Diane Willen, “Godly Women in Early Modern England: Puritanism and Gender,” the Journal of Ecclesiastical History, 1992).

Third, a note on pneumatology and Puritanical Calvinism. Cessationist theology will never rest well with Quaker theology (even with seventeenth-century bundling practices? This is a niche history joke). It won’t rest well with any theology of charism. If the Holy Spirit was done pouring out gifts at the end of the book of Acts, first of all I have many – many – questions about consistent interpretation of large swaths of the New Testament, but more to our historic point, if your theological starting point is that the Trinity went silent millenia ago, then of course you’d assume it’s impossible for the Holy Spirit to shed inner light in the hearts of women and men who are Quaker; impossible for the Holy Spirit to put a message on their heart to share.

Fourth, a brief note on the Euthyphro dilemma, Calvinism, “o felix culpa,” and the New Testament. [warning: brief mention of sexual assault.] Is something good because God loves or commands it, or does God love or command the good because it is good? This ancient philosophical question (remixed as monotheistic rather than “the gods”) is also lodged in Christian theology. What is the source of goodness? If God loves or commands xyz, and therefore it must be good because God loved or commanded it, then xyz may be a one-off ineffable mystery of divine sovereignty that does not affect the whole. If God only loves or commands the good because to love or command otherwise would contradict the internal nature of God as wholly good, then God is not the author of evil; and if something is not good and does not resonate with the revealed nature and character of God, then perhaps it is not of God.

Eventually, consistent Calvinists face a crisis; sometimes the result of it is the conscientious Calvinist-to-universalist pipeline, because of the philosophical, theological, moral, and ethical quandary that arises: does God predestine evil? Atrocities? And if God does, how could God exclude anyone from an afterlife of happiness if God is the one causing the evil we do? Causing…

War crimes?

Robbery?

Sexual assault?

If I believe that something is good because God loves it or commands it – regardless of whatever it is – then the grounding of that goodness isn’t in the character of God, it’s in the command, choice, or whim of God.

Kind of like, “respect the position even if you can’t respect the person.”

Or kind of like, “I’m just following orders and the chain of command, it’s not my job to question whether or not to attack these unarmed civilians.”

So if I’m a patriarchal, Puritanical Calvinist reading about Deborah or Phoebe or Junia, if I’m tempted to read about those women at face value, even if I take their leadership at their times at face value, I may take those examples as “descriptive, not prescriptive.” Because after all, God is free to do whatever, even to include women in Romans 16. I can rest easy that all the women in scripture don’t actually say anything about who God is. I can sleep peacefully, knowing that Junia was a misunderstanding sent to test and try us, because God works in mysterious ways - or rather, God worked in mysterious ways, but cessationism lets me say God stopped working in those ways, thank heavens, because can you actually imagine Mary joining you at Jesus’ feet instead of helping Martha in the kitchen where she belongs?! Of course not, it would be against nature itself. (Now, I spent a whole semester hip-deep in Calvin’s Institutes, and I’d still be tempted to ask why, in God’s sovereignty, God couldn’t start up again after having cessation’d - what’s stopping God from pouring out the Holy Spirit here and there if it so pleased the Almighty? But apparently the fog of ineffability and inscrutability lifts a bit when patriarchy is involved.) If I’m a patriarchal, Puritanical Calvinist, I can rest assured women in the text are quirks - but definitely not signs of anything overarching, and not signs of anything about God.

And if I’m a consistent patriarchal, Puritanical Calvinist, the same God who, perhaps, predestined Deborah or Phoebe to do whatever they did (that egalitarians interpret as leadership), also predestines other things in the world just as baffling – things like atrocities, or abuse, or assault.

Unfortunately, both Calvinists and Arminians have at times echoed an ancient, poetic sentiment first expressed in Catholic theology: o felix culpa, Latin for “o fortunate crime,” or “o, lucky guilt,” or often, “fortunate fall,” as in the fall of humanity in Eden. Oh fortunate guilt! That lets us know Christ as our redeemer. Oh fortunate fall of humanity, through which we are blessed to know our Savior. (As though our knowledge of the Second Person of the Trinity would forever be insufficient without our own sin as an avenue to know the Word! – “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” To claim our sin is a necessary condition to know the Word is to idolize broken human selfishness and to reflect a diminished moral and theological imagination. I have strong words for Mr. Wesley on this when I see him in The Great Beyond.)

But I don’t know any ethically, morally, pastorally responsible individual who can stand up and say, “o fortunate genocide!” or “o fortunate child abuse!”

In an Arminian framework, the reality of evil is not diminished; but neither is God’s sovereignty. There are a range of Christians who believe in the genuine operation of actual human free will – some Orthodox Christians do not believe in original sin or total depravity; classic 18th century Methodism believed in both – but also that God’s grace preserved the imago Dei meaningfully enough to preserve genuine free will.

What do we make of the character of God?

What do we make of human freedom?

Women are not grist to be ground for God’s glory.

(Neither, as it happens, are men.)

In class-conscious, hierarchical 17th-century England, it was theologically explosive for Quakers (and Baptists) to say that women could hear the voice of God without a priest – or without their husband. This was in direct conflict with Calvinist cessationism. And in a context of overlapping ChurchAndState, to practice Christianity outside the OfficialChurchAndState was a matter of patriotic suspicion: are you a religious fanatic, or are you against the current monarchy – or both? Quakers rejected the idea of ordained clergy, bulldozing hierarchy, sitting in silence, allowing women or men both to speak or to stay silent, as the Spirit moved. The Conventicle Acts were designed to restrict meeting for worship in settings outside the Church of England (there’s a reason that later leaders in the U.S. specifically noted rights to freedom of religion, freedom of assembly, etc.).

On the day Deborah’s back was beaten as she hauled garbage through the streets half-naked, the constable was the proximate cause of her suffering. But behind him stood patriarchy propped up by the twin theologies of predestination and cessationism.

No wonder they hanged Mary Dyer.

Somewhere around 150 years later, formerly enslaved preacher Old Elizabeth had this encounter: “As I travelled along through the land, I was led at different times to converse with white men who were by profession ministers of the gospel. Many of them, up and down, confessed they did not believe in revelation, which gave me to see that men were sent forth as ministers without Christ's authority. In a conversation with one of these, he said, ‘You think you have these things by revelation, but there has been no such thing as revelation since Christ's ascension.’ I asked him where the apostle John got his revelation while he was in the Isle of Patmos. With this, he rose up and left me, and I said in my spirit, get thee behind me Satan.” (From her memoir, which you can read here.)

Formerly enslaved Old Elizabeth shut down the white minister with logic drawing from scripture. Those men may have been sent forth without Christ’s authority, but she wasn’t.

When Even the Threat of Prophetic Nudity Ends Bloodshed

If I could stop a war by peeling off and walking into rubble in my birthday suit, would I? My memory verse-laden, revivalistic childhood has grown enough from letter of the law to spirit of the law to be able to say, “yes–of course!” If I could stop people dying with my own nakedness, of course I would. Jesus would sigh and get a migraine if I were unwilling to for the sake of legalism. It would be leaving my neighbor’s donkey in the ditch, it would be staying hungry instead of plucking grains on the Sabbath, it would be a gross miscarriage of love.

In fact, it would neglect the model of Jesus Christ, executed naked for a bruised and bleeding and violent world of humans.

Few of us have the opportunity to stop war with even the threat of the sight of us in our “altogether.”

Few…but not none.

About twenty years ago, women stopped a war – in part, with the threat of nudity.

Now that’s prophetic nakedness.

From “How Nobel Peace Prize Winner Leymah Gbowee Unified Liberian Women”:

“2011 Nobel Peace Prize winner Leymah Gbowee forged a new path to help bring about the end to a brutal civil war. ‘You go to bed and pray that you have something different the next day. You know, that the shooting will stop, that the killing will stop, that the hunger will stop, saying, “God, please,”’ Gbowee says. ‘I had a dream. And it was like a crazy dream, that someone was actually telling me to get the women of the church together to pray for peace.’ And that’s exactly what Gbowee did. Starting in 2002, she brought together thousands of Christian and Muslim women to peacefully protest and pressure religious and political leaders to stop the 14-year war that had led to mass gang rapes of an estimated three-fourths of the country’s women and girls, the conscription of young boys in Taylor’s marauding armies, homelessness for nearly a third of the country, and the deaths of at least 250,000.”

From nobelprize.org: “[Gbowee] then collaborated with a Muslim partner to build an unprecedented coalition...giving rise to the interfaith movement known as the Women of Liberia Mass Action for Peace. Leymah was appointed its spokesperson and led the women in weeks-long public protests that grew to include thousands of committed participants. Leymah led the Women of Liberia Mass Action for Peace participants in public protests that forced Liberia’s ruthless then-President Charles Taylor to meet with them and agree to take part in formal peace talks in Accra, Ghana. She led a delegation of women to Accra, where they applied strategic pressure to ensure progress was made.

At a crucial moment when the talks seemed stalled, Leymah and nearly 200 women formed a human barricade to prevent Taylor’s representatives and the rebel warlords from leaving the meeting hall for food or any other reason until, the women demanded, the men reached a peace agreement.

When security forces attempted to arrest Leymah, she displayed tactical brilliance in threatening to disrobe – an act that according to traditional beliefs would have brought a curse of terrible misfortune upon the men. Leymah’s threat worked, and it proved to be a decisive turning point for the peace process. Within weeks, Taylor resigned the presidency and went into exile, and a peace treaty mandating a transitional government was signed.”

Learn more about Gbowee in her memoir Mighty Be Our Powers: How Sisterhood, Prayer, and Sex Changed a Nation at War and about Gbowee and other Liberian women in the documentary, “Pray the Devil Back to Hell.”

According to her Columbia University World Leaders Forum bio, “In 2007, Leymah earned a Master’s degree in Conflict Transformation from Eastern Mennonite University in the United States.”

I think she’d already mastered transforming conflict.

And I think that 17th-century Quaker Deborah Wilson was smiling from the gallery of the saints.

Mighty be our powers indeed.

Elizabeth Glass Turner, M.A., is a writer and editor. In late 2023 she launched season one of FireFall, a newsletter amplifying resources by, for, and about women in pastoral ministry and church leadership. She is credited as “book doula” for Live Anointed: How the Holy Spirit Sanctifies Men and Women to Lead Together by Rev. Katie Lance; contributed entries to the latest edition of The Historical Dictionary of Methodism; an essay to The Philosophy of Sherlock Holmes; a chapter to The Sound of Revival: Seven Powerful Prophetic Proclamations; and a chapter to The Journey of Grief: Traversing Our Sorrows Together edited by Tom Fuerst, Chad Foster, and Jonathan Powers. She was also line editor for This Holy Calling, a collaborative devotional volume by women in ministry for women in ministry and was developmental editor and copy editor for the original printing of Saints Alive! Thirty Days of Pilgrimage with the Saints by Maxie Dunnam. Elizabeth has interviewed figures like Narnia producer and C.S. Lewis’ stepson Douglas Gresham as well as author Kay Warren. She has met the late Sir Antony Flew, the late Charles Colson, the late Rev. Dr. Marilyn McCord Adams, and the late Father Richard John Neuhaus. However, the first person she was ever excited to meet was Roscoe Orman - better known as Gordon, from Sesame Street.

She has pastored a small rural church through revitalization, worked with international students in campus ministry, collaborated across denominations as associate director for community and creative development at World Methodist Evangelism, and crafted speeches and content for higher education, for-profit, and non-profit entities as well as B2B digital transformation thought leader content.

Currently, Elizabeth is getting ready to launch season two of FireFall newsletters. She is also developing a book with the working title She-Preachers: Seven Snapshots of Women & Spiritual Authority.

A NOTE ON SETTINGS: If you subscribe to Elizabeth Glass Turner and wish to receive FireFall newsletters, please check your Substack settings to ensure the slider for “FireFall” is clicked “on.”

I am so thankful for paid subscribers who support this work! If you’re able and haven’t yet, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription so I can continue to invest my time in writing.